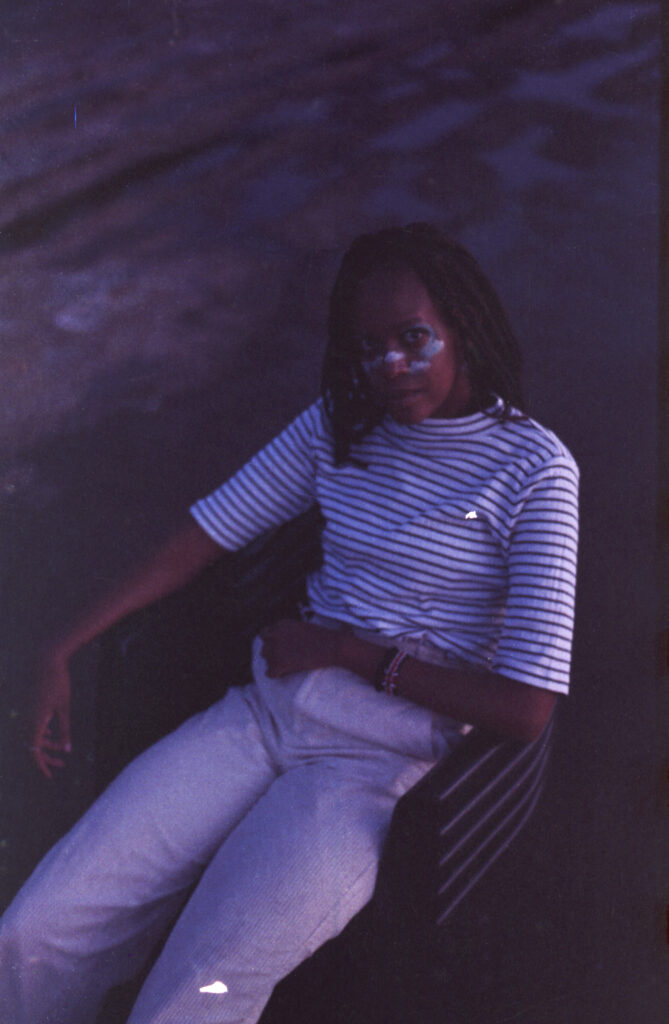

By John Eni-ibukun

Nyokabi Kariũki doesn’t think of music within its traditional spectrum. Rather, she loves to work with sound generally (not just music as a form of it). Her art revolves around exploring all the possibilities through which sound can be used as a medium for expressing and communicating. Nyokabi’s art, simply put, is a continuous way of fun seeking, an attempt at memory preservation and a medium of deep expression through sound experimentation.

Her newest project which she titled peace places: kenyan memories can objectively be described as a time machine through which the composer protects and preserves memories of moments she spent by herself, with family and even a moment in which her childhood friend, Naila Aroni (who made the cover art for the project), spends with another friend. In essence, the project is a collection of past experiences through recordings made in places that are important in helping her relive, imaginatively, her formative years. Through it, her culture is also preserved.

I connected with Nyokabi digitally, through the Zoom app on a hot afternoon, I recall. We had a conversation surrounding her art and her most recent body of work.

Through our conversation, I was able to live a little in the mental world of this artist from Kenya who is actively disregarding the influences of the institutions that have taught her classical ways to fine tune her art. She is doing this in the most agreeable manner through peace places: kenyan memories, her experimental project which blends so many elements of her African cultural roots, placing them overtly above the background sound of music. This article is a documentation of that conversation.

Hello Nyokabi, Good afternoon (it’s afternoon over here). My first question, naturally is this – it is quite evident that you are an artist and composer. Let’s imagine that you meet a person who knows you as an artist but hasn’t had the time to check out your works – how would you describe yourself, in relation to what you do, to them?

Hmm. That’s always an interesting, difficult question to answer given how much my work has been changing over time. I guess I would maybe say to someone who hasn’t heard my work before that I work with sound. I am a composer that sort of sees the value in these everyday sounds and instruments, including our voices and languages – in everything really. And in a way, that’s not how we traditionally think of music, but yeah, I work with sound and I enjoy discovering the possibilities with that medium of expressing and communicating.

That’s quite profound. I think ‘Equator song’ was released off the project a few weeks ago, on a Wednesday, if I’m not mistaken…

Yes

How was its reception when it was released? How did your listeners and friends react to it? Also, how did it feel to you personally, putting out something new?

The reaction was surreal. I was very curious about how people would react to this, especially people from home, but it’s been positive. My dad and my brother are just saying my music is weird (laughs). I think it’s nice, it’s a nice thing. I’m used to getting that, I’m OK with it. But I’ve also had friends who found it beautiful and felt they enjoyed how I mixed the sounds of the birds leaping into the sounds of the voices.

I think people have also said it’s interesting as well. I’ve gotten a lot of “this is interesting” and also, you know, people have connected to it because, in the piece, I sort of talk about these feelings of displacement or disconnect to my languages, even though I’m opting to express them in them.

Like on Twitter, someone had commented. The piece premiered on a BBC Radio Six programme, which was amazing. It was very surreal. The tweet read “As someone who calls many places home, it struck a chord”. I really appreciated hearing that it resonated with people, especially Africans who have also kind of experienced something similar in that regard of you growing up in a place where you don’t know so much of your own culture just because of the history of colonialism and the after-effects of that.

Oh, that’s so cool!

Your project is titled peace places: kenyan memories. After listening to it, I imagine it was an attempt for you to revisit memories and carefully curate them in one space, sort of like a time machine. It is a collection of recordings of sounds you’ve gathered over time while revisiting the places and people that have been important to your formative years, and now as an adult, it helps relink you with your culture.

I would love to understand your personal story – the story of growing up and having to move between places. From your own standpoint, can you tell me about these experiences that have molded you into this person and artist you are?

Okay, so I grew up in Kenya, 18 years of my life. I’m twenty-three now, so I went to school here in Nairobi, then I went to New York University for my undergraduate degree in music composition. I love traveling, I mean, travel has always been something that’s a part of my life. My parents have always enjoyed it, and found it important that my brother and I sort of saw the world in that way. So that’s something that was a part of it. And then when I moved to New York, I also saw and learned so much about the wider world. So traveling is quite a theme of my life and something that I love to do.

I think one of the interesting things, though, is the fact that I grew up in Nairobi, but I still, sort of felt that disconnect because of the institutions that I went to. I went to international schools, recognizing the privilege that it was to be in some of these schools; but you go to the schools and you’re meeting people from all over the world, but at the same time, what you’re learning is not necessarily connected to you, but you think it’s normal because you don’t know otherwise.

You know, especially in this case, and I always zone in on music education. The music schools I was familiar with in Nairobi were teaching primarily Western classical instruments, and we took yearly exams that were designed by an exam board in the UK. So that’s the system a lot of us who studied instruments were taken through, and that’s the way I learned how to play piano. The teaching was based around the Beethoveens and the Mozarts, and that in a way is what I mean by this displacement. Because you think that that’s the only thing that you are supposed to learn, and that was the only right way to go about it.

Over time I started to realize that there’s so much more that I wish I knew and that I wish I had learned which I’m now putting the energy and time and effort into understanding. Looking back at music makers from Africa, seeing how I can learn from them. I’ve heard from some people who had a similar story to mine, in that even while they went through an education system designed by a Kenyan body, the education on African music was not necessarily given the attention and respect it deserved. It’s also important to say that I have also spoken to other Kenyans studying music who have a different perspective, where they say that they went through a musical education that offered the learning of many traditional instruments, and they have teachers who are encouraging it. So I’ve just been talking to a lot of people and learning more about how music education is within the country. I hope for there to be a variety. I think what’s important is that we are having all these perspectives that if you want to specialize in Kenyan music, you can, if you want to do Western music, you can. But in my experience I just think there was a lot of that displacement because I didn’t get to see many options.

Yeah, I think it also has to do with the institutionalization of Africa generally. There are limited major institutions that are willing to document all the things happening within the musical entertainment scene. Also, I’m of the opinion that there’s this, should I say, imperialist mindset where things that come from outside of Africa are more valued than the ones created here…

I believe things are changing gradually in this regard, and am also optimistic about we as a people trying to rethink. It’s also important that we make people see reasons why we can’t afford to think that way. And that brings me to what you said about people just playing Beethoven and, you know, the main classical guys. I’ve also observed that many of the African musicians, dare I say composers, used to draw inspiration from the Western culture to create sounds that are unique – this is evident in African genres such as Juju and Afrobeats. With this project, you kind of tolled the same path creatively by drifting away from the dictates of the western world that has to do with, you know, making music with a universal language, which is English, French, Italian, Spanish or other languages like that, choosing rather to express in more intrinsically local dialects…

In terms of your plan for the project, was that intentional or was this just the case of “Okay, let me just express in this language and see how it goes”?

Hmm. I think it was definitely intentional because in this journey of me learning about my culture, language is so closely tied to that, and it’s something that I think about very often. I really love language, and I think it shows in so much of my music. So yes, I would say it was very intentional because, you know, in college, a lot of the vocal music I was writing, pretty much all of it was expressed in English. So I thought to myself, let’s see how it feels to start expressing in Kiswahili, and in this EP, you will hear some field recordings of my grandmother and my mom, my dad speaking Kikuyu. Which is the language of my ethnic group. And then even in the single ‘Equator song’, I’m speaking in Maa, the language of the Maasai, which was such an interesting thing, where I’m saying numbers, you know, in the song, (“Nabo, are…[one, two]”), as a way of tracing the words that some of my Maasai ancestors may have spoken.

I just think of the fact that some of these Kenyan languages have not been heard sung in experimental contexts. I’ve only heard them in traditional music, which is beautiful and rich, and then I’ve certainly heard Kiswahili (and Kikuyu, to a lesser extent) in contemporary pop music, but I enjoyed sharing these languages and having fun with them, and using them to express certain ideas, regardless of whether they are universally known or not, in ways that we had not perhaps heard them in before. Our own stories and our creations, our languages can be used in music, can be used in what I hope is seen as a beautiful and fulfilling way. So, yeah, it was quite intentional because of that.

That’s very interesting to note.

Listening to the project generally, I think that asides the music you needed to just express some other feelings that could not have been arranged in scales and melodies. Evidence to this is that a large percentage of the project are recordings of everyday transient sounds as opposed to just singing in its particular term. There are things that the project express that go just beyond the music. So how would you describe it – ‘peace places: kenyan memories’ – as a project?

I would describe it as music, all of it as music (laughs). I understand what you’re saying. As I mentioned earlier, I would say maybe sound art; making art with sound. I think there’s a certain beauty in listening to things beyond what we traditionally term as “music” – because I think we take sounds for granted a lot of the time. But there’s so much richness in the sounds around us, and so some of the songs — if not all of them — include recordings that I took with my phone, some of them were from videos that I was taking with my phone casually like on holiday, like, “oh, I’m by the water or I’m in the village where my dad grew up, let me take a video”. I sneak audio from some funny moments in these places, such as in the track “Ngurumo, or Feeding Goats Mangoes”. There’s this audio from a video of me and my brother feeding mango peels to some goats in the farm in my father’s hometown, because it’s like a fun, silly thing to do.

So for me, that was it. It’s like discovering that there’s so much music in everyday sounds (and we are most times oblivious of that). The EP was me trying to find that music in these sounds that are around us. So all of the sounds that I had in each track were from Kenya. Okay, there’s only one field recording where I cheated: in “Naila’s Peace Place”, the final track, there’s the sound of trees blowing in the wind, and I took that recording in the U.S. So that’s the one that cheated a little bit. But apart from that, all the field recordings were taken in places in Kenya that the tracks are based on.

The recordings of those everyday sounds were what caught my attention. Before this interview, when I got the pitch for this interview, the whole concept of the project caught my attention, and I kind of resonated with it because when I visit places, I also love to collect sounds – of nature and conversations with people…

Wow.

Yeah, I do that very often. I just record sounds. Just for the fun of it.

Yeah, I love that.

So I listened to your EP but obviously, I do not understand everything about it because, you know, most of the songs were created in languages I neither speak nor understand. But then the sounds of the birds, the ocean, the trees, the wind – these are sounds of concepts that are universal. Anyone would understand what they represent. However, essence of project lies in it’s stories. Would it be okay if I asked that you describe the story around which each each song was created and the memories they represent?

Yes, absolutely. All right, thank you. The first track is called Equator song. In this song I speak in three languages; English, Kiswahili, and Maa— which is a language of the Maasai people. This track came about in December 2020. I visited Laikipia, which is a county in Kenya, and it’s on the equator. So that’s why it’s called ‘Equator song’. It was a very interesting time because… how do I explain this for non-Africans? When you start talking about tribes, I think a lot of foreigners are like, “Sorry, what? What’s that?” (laughs) But my name is Nyokabi, which is how the Kikuyu would refer to people from Maasai land. I’m named after my grandmother and she was named after her grandmother, and it’s kind of a pattern in that way. But my grandmother’s parents had Maasai heritage, which is how the name was passed down to me.

So when I was in Laikipia, which is a county where there’s a large Maasai population, I was just thinking a lot about that; my name and that connection to the land. So in the song, I’m saying “you’ll find my soul on someone’s tongue”, in the sense that there’s a lot of my own story that I can’t tell you, both because I don’t speak my native languages and because there are elements of loss and erasure that happened in my ancestral history. Then at the end of the song, when I start to count in Maa, I think it was just the fact that these are words that my ancestors, my Massai ancestors may have spoken, right? I don’t know this language but I thought that maybe this was a way that I could kind of trace that connection.

So that’s the first track. The second track is A Walk Through My Cũcũ’s Farm. It’s pronounced “shu-sho”. So this track was based on when I came to Kenya in December 2020 as well. The first Christmas during the pandemic. It was very interesting because, you know, I’m sure you remember when the pandemic hit, all travel just got canceled and I usually come home in the summer and then over Christmas. So, you know, this is the first time that I had gone to the US that I was not coming back in the summer. I didn’t know when I was going to come back, I think there was so much uncertainty around the pandemic and I think something that was a really big theme, and that still is a big theme in this pandemic is our grandparents and their vulnerability, you know, because of COVID. So when I was able to come to Kenya in December, you know, it’s always been a family tradition to visit her every Christmas. We were able to go safely, and it was just a very meaningful visit for me, I think because there was so much that I was seeing in a new way, because of the pandemic.

So that track features sounds from that day when I was just recording things. You know, we were walking around her farm. She’s showing us her avocados, her maize, her sugarcane. I was just filming that casually and never intended to make a track out of it, but when I got home, it just happened. In the piece, I then narrated the experience very simply in Kiswahili. You hear me say “maparachichi” a lot, and I laugh a little when I say it… it means ‘avocado’ in Kiswahili, which I think is a very pretty word. It’s my favorite word in Kiswahili. So it’s kind of like what I was talking about earlier, me playing with language and interacting with it beyond its meaning. It doesn’t only need to be used to communicate things, it can also be a fun thing, you can play with the sounds and the cadences and the way it feels. That’s the second track.

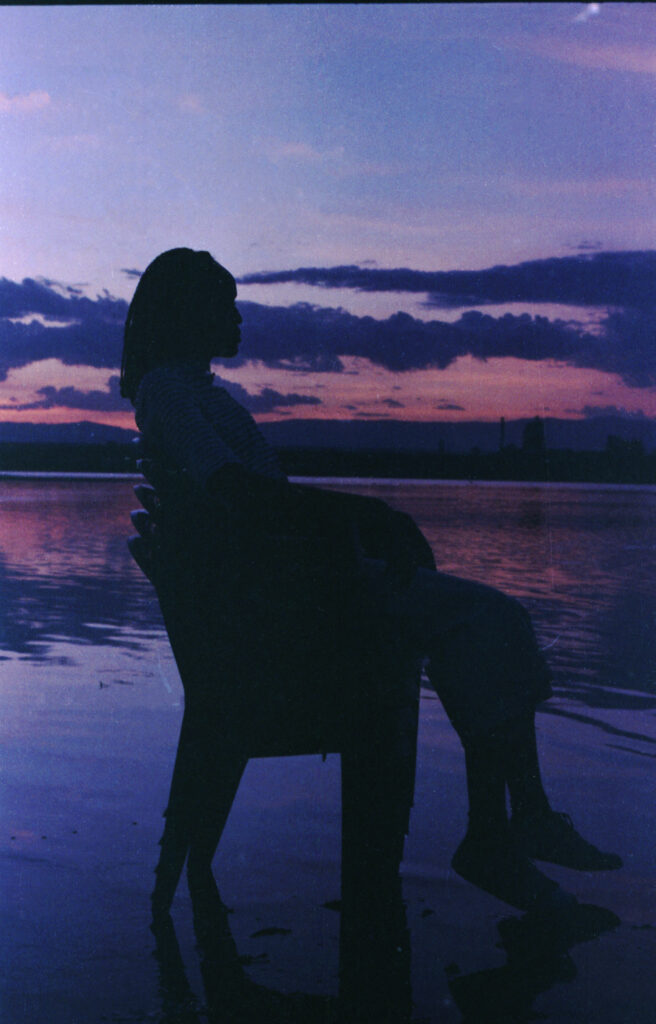

The third track is Galu, which came out last year on SA Recordings, the label releasing the full EP, as well. The track is based on this beach on the Kenyan coast called Galu. I love going to the coast. It’s a beautiful place in Kenya, and I mean, there are a lot of coastal towns and a lot of places you can visit.

That was the first track that I wrote for this EP, actually, Galu, and it’s what kicked off the whole project. So, yeah, it has field recordings of me when I was wading through the water on the beach, and it’s just a very peaceful song in a way. I think it’s my most peaceful song on this record because the others, I think, are engaging with more kind of some of the friction with language like I’ve been talking to you about and stuff, but this one was just very much like, I’m just swimming, just imagining myself swimming in the Indian Ocean and just enjoying that peace.

The fourth track is Home Piano. You know, my first love is the piano. That was the way I walked into music and sound. I’ve always felt there is a very unique relationship that my fingers have with the piano that I have at home, more than any other piano I’ve played on. I was gifted this piano when I was eight. I started the piano when I was five, and you know, my parents gifted it to me as they saw it as a worthwhile investment to make, and that changed my life. I’m getting emotional thinking about it. But yeah, I guess going abroad, even just playing on so many different pianos, I don’t know how to explain, but there’s a very specific relationship that my fingers have to this piano at home in Nairobi, and it feels like home.

So that’s what that track is about. So you hear me playing it on a rainy day; I decided to record myself playing with the door open so you could hear the rain, and I wanted to have that effect of maybe just how it is to listen to me playing the piano at home, you know, my parents, my brother would always have just heard me play. So that’s what that one’s about.

Track five is Ngurumo, or Feeding Goats Mangoes. That’s the title Ngurumo, which means “valley” in Kikuyu. Where my Dad grew up there’s this walk that we used to do, we’d walk down the valley in our gumboots and there was always forest around us. Then we would sometimes swim in the river or if the water’s too cold, we just drink from it or just have a good time there. It’s such a peaceful place for me.

One of the visits we had, there were some goats, so that’s where we were feeding them these mangoes and in a way, that’s why I’m speaking in Kiswahili, and I’m kind of repeating a very similar motif – “siku za…” meaning “days of…” and then I change the word, “days of the mountain”, “days of creation”, “days of rest”, and so on. So the song basically is just me longing to return to these places; and the higher voice I sing, “return me to the days of peace”. That’s something that I am saying repeatedly in that song and in that song, I’m also using the mbira, the African thumb piano from Zimbabwe. I was collecting different African thumb pianos at some point last year, using them in my exploration of different types of African music and kind of learning from these instruments. So that track uses the mbira quite heavily.

The last track is called Naila’s Peace Place. It’s based on the ‘peace place’ of my friend, Naila Aroni. She painted the artwork for this album. Um, and it’s gorgeous artwork. She is such a big part of this because she created three paintings based on three tracks from the EP, based on the stories from the places and colors that I was imagining for the music. So I wanted to honor her in return by asking her, “what’s your peace place?” and making music around that. So I asked her to send me any videos she’d taken from her peace place, and she sent me some. Her peace place was another coastal town in Kenya, called Lamu, and I’ve never been there, but it’s stunning. I really want to go. It’s a very unique place. You can’t have any cars in Lamu. You can only get around by walking or by donkeys or by boat. And it’s got a unique culture, and pace.

She sent me some videos, but there’s this one video where her best friend, as you hear in the song, says, “Naila, how happy are you, are you?…This place doesn’t even feel real,” or something like that. And to me, that was so beautiful in a way, I was like, this is what the track is going to be centered around. I just felt like this was a sound of joy. You know, these two best friends, walking in a place and they’re saying that it’s surreal and you can hear that joy in their voices. So actually in the piece, we have some dreamy vibraphone, which was played by US-based percussionist, Chris O’Leary, a very talented performer who I enjoy collaborating with. Then you hear these ‘yells’ or ‘howls’, which is really just the same audio of the conversation between Naila and her best friend — I time-stretched the audio as a way to sort of freeze that moment in time, so we could just sit in their joy.

So that’s the final track. Yes.

Thank you very much for running through this for me. From all I’ve gathered, the entire project is a collection of different blends of instruments, languages, sounds and each element of experience expresses or represents something. Generally speaking now, what matters to you the most and why?

Home. This is such a funny answer, because, to me, home is so many different things —— that I find a home in my family, I find a home in my friends, I find a home in music, I find a home in my languages and in where my dad grew up and where my mom grew up, and where I grew up. Yeah, I find home in so many different things, and I think that’s what matters to me the most.

That’s profound.

Yeah.

From these stories I can tell that this project is very personal to you, yeah?

Yes.

Now, you’re putting it out there, who do you think your audience are? in terms of reaching out who are those you are hoping to reach through this project?

I don’t know. I think anyone who is willing to listen. I think that my music, I don’t know how to classify it within genre. I don’t like the idea of genres. I think genres are based around industry marketability. I think when you have something like this, I mean, I don’t know, would you classify it as? I don’t know how to classify a work like this. I think that genre makes it easier to say, Oh, this is the audience for this music. But for something like this, I sort of want to challenge that and say that if someone is willing to listen then that’s my audience, it doesn’t matter what they typically listen to.

Of course, it means a lot to me when it’s Africans listening, when it’s people from home because I want them to be able to see themselves in the music and I want them to see that it’s not only popular genres that is the only way to engage with music. There are so many different ways to experience sound. There are so many artists from Africa who are making experimental music — some of my favorite experimental musicians in Nairobi right now include DJ Raph, KMRU, 7headc0, MONRHEA, Nabalayo — and we can engage with their music, despite the fact that it’s not in the mainstream. So I think that is always very special.

When I’m hearing that my friends who mainly listen to rap or afrobeats are like, ‘I really liked this’, ‘I really really loved how you did this’, or ‘it touched me’, or ‘I felt like I resonated with it’, or ‘I enjoyed it’, it makes me happy. But also for me, it’s like, even though you didn’t enjoy it or if you find it ‘weird’ — that’s OK. Like, I just want there to be engagement with the music; that you listened and it made you think and form an opinion. So yeah, I don’t have an audience in mind, I think anyone can listen to it and have their own experiences with the music.

Now, to my last question. This is about your art now. Your art as a composer goes beyond just music. The spaces of entertainment that it can take expands beyond just the Music in terms of getting streams and getting royalties, and you know, the cliché lingo of general everyday entertainment. In your own terms, Where do you think, or should I say, what avenues do you think that your expression can take you? Where do you envision your? In what other spheres can it be applied? Like if you had a vision board – without overthinking it – in what places will you joyfully place your art for use?

Wow! Ok, I see what you’re saying. So many, there’s so many, and this is one thing that I discovered when I went to New York University – just how big the world of music is, and I’m so curious about so much. When I went to university initially, I thought only film scoring was how composers existed today; the only kind of composers. But I learned that’s far from the truth. And so I’ve been very lucky to work with film scoring, yes, but also writing for the concert stage, with writing for choreographers, to something like this, an EP where it can be listened to in so many different ways. And I think I see it being that way in the future. I see myself kind of being flexible and expanding the spaces in which I’m making music for, you know. It could be installations, it could be for sound art, radio as well. I think it’s very open for me. It’s very limitless. I think that’s maybe been the fun thing about feeling that I don’t work within a defined genre because I think I get to define what my own music is, where my music goes and how it can be experienced, so I guess we’ll see. I don’t have an answer for you because I think I’m enjoying the openness here.

So to you the road is broad and you just want to take the path that leads anywhere as long as it aligns with what you are doing…

Yeah.. as long as it’s true to myself and the music, I am so open.

All right, then. Thank you Nyokabi for for taking your time to have this conversation

Yeah, thank you so much too. I really love Drummr and I am honored that you chose to have this interview. Sawa sawa, Asante!